Why You Never Really Forget Old Choreographies

A deep dive into muscle memory and the mysterious ways we retain dance

I’ll admit it.

I haven’t been dancing at all.

For someone who started a newsletter all about dance, there hasn’t been much dancing. This is completely different from what I pictured. I had this vision of getting fully back into it with a renewed sense of purpose, and that’s yet to happen. Until halfway through writing this post.

Every time circumstances push dance to the back burner, there’s a voice in my head that says, “If you’re out of practice, you’ll eventually forget everything.”

But that couldn’t be further from the truth.

Basic coding-related questions have me digging through the depths of my brain to pull something coherent out. But old dance routines resurface out of nowhere when I hear those songs.

My body slips into a trance. My eyes take on a faraway look. I succumb to the music, and my limbs begin to move of their own accord.

This is probably why the Youtube video of the former ballerina with Alzheimer’s instinctively recalling the Swan Lake choreography really stayed with me. I had tears streaming down my face watching it, knowing that exact feeling of how certain pieces cannot be erased from your body. All it takes is for the music to start, and an eerie sense of physical nostalgia floods in, taking over completely.

As a dancer who is often out of practice, there was something deeply reassuring about that video. The idea that your brain can deteriorate in terms of language, memory, and skills, and yet the choreography you repeated countless times still remains.

I myself have gone through this cycle so many times before — stepping away from dance and then returning, only to find that my body remembers far more than I expect.

Riding a bike pales in comparison to remembering choreography. The dynamic involvement of so many body parts, all working in sync, must be such a complex process in the brain. And yet, once learned, these movements are engraved so deeply into the body that they become second nature. That’s what truly fascinates me.

So I had to dig deeper. Because it doesn’t feel like dance lives only in the brain or the body. It feels like it’s stored somewhere else entirely.

Like the memory of it lives in the spirit.

Where Does Choreography Live?

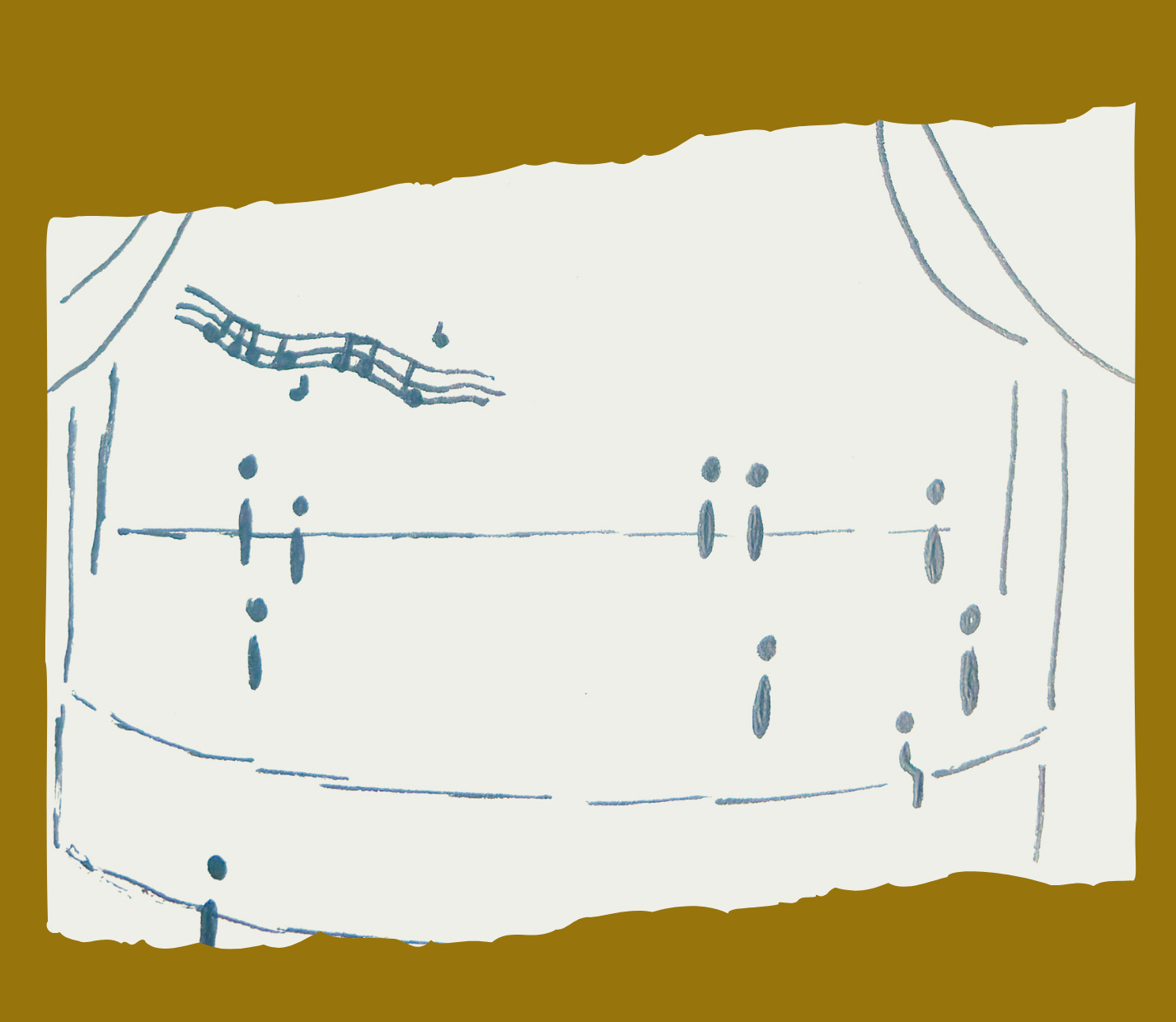

I had to understand how exactly muscle memory works to figure out what really happens to our bodies with these movements are engrained in us. Based on my mini biology lesson gained from watching videos and skimming through papers, this is how I’ve mapped out muscle memory to my understanding of how it works in our bodies:

But if the brain is evidently still involved, there should be some aspect of having to jog some memory, right?

Apparently not. Not if you’ve run through the choreography several times because at that point it becomes second nature.

Memory is divided into conscious and unconscious types. The kind where you’re actively recalling, remembering, or “searching your brain” falls under conscious memory. Muscle memory, on the other hand, is a form of unconscious memory known as procedural memory. It allows us to learn and perform skills without needing to think about them consciously.

This kind of memory is exactly what distinguishes an amateur from an expert. An article I found referenced a study comparing professional and amateur violinists. Researchers found that the key difference between them was how automatically professionals performed. Their movements had become so deeply ingrained that they no longer needed to think about each action. The amateurs, on the other hand, still relied on consciously processing the action as they played the violin.

If you’re wondering how professional Indian classical dancers are able to focus on the storytelling aspect while performing complicated, stamina-intensive intricate footwork sequences, it is because they’ve practiced it so much that they are able to zone out of the physical movements, allowing room for conscious thinking to embody a character or focus on the emotional narrative.

This is typically where you have space to find your style as a dancer. Do you prefer a subtle display of emotions? Are you likely to challenge or subvert people’s perception of the character? How would you react in this situation? And how would your character perform this footwork sequence?

“With enough repetition, the music is inevitably linked by some mysterious connection to our muscle memory so that eventually, we don’t have to think about the steps. Our bodies know what to do, leaving our brains free to give flight to our imaginations in performance.” — Jennifer Ringer, Dancing Through It (2015), cited in The Guardian

Irina Ma’am and the Art of building Muscle Memory

There’s no exact guideline for developing muscle memory for dance (though interestingly, I did come across an informal one for video games that had surprisingly relevant insights).

So I had to read up a couple articles to compile all things that might contribute to improving muscle memory and I started connecting the dots. Oddly I kept thinking back to the techniques that my school dance teacher followed.

Without realising it at the time, I had experienced the development of muscle memory through the methods she used to train us.

I usually avoid using people’s names in my posts because I like to preserve a sense of anonymity. But this teacher and her approach were unlike anything I’ve ever seen. As I read more about muscle memory, I kept recalling how closely her methods mirrored what the research was describing. So many techniques she used came rushing back, each one confirming how deeply effective her methods were.

The context

We were 10 girls between the age of 12-14 with 3 months left to learn and perform this intricate Garba1 choreography. The complexity was in the formations and uniformity which demanded group effort of knowing the choreography very well. So how did she do this?

Repetition

Pretty much any advice I read or inquired about on building muscle memory boiled down to repetition. How many times? It really depended on the complexity of the skill. But repetition is essentially what helps you remember choreography.

This dance teacher had a knack for drilling the choreography into our bodies. After teaching us the entire piece, she would conduct intense rehearsal sessions where we’d run through the whole routine until we got it right.

If, during a run-through, she spotted one member of the dance team making a mistake or not performing up to her expectations, she would pause the music and call them out.

This would be followed by a swirl of her index finger accompanied by her saying, “From ze beginning,” with a strong Russian accent, and we’d have to start all over again.

Through these sessions, we rehearsed so many times that when the performance finally came, we relied so heavily on muscle memory that we didn’t even have to think. I recall during the last stage rehearsal before the performance, the only issue was orienting ourselves on the stage since we were used to a different-sized one.

Switching up the routine

With Irina ma’am, you never knew what to expect during practice sessions. You could almost see the cogs turning in her head as we walked onto the stage, and the air would thicken with tension before she spoke.

She’d purse her lips to hold back a smile before throwing a new challenge our way.

Like when she sat on the stage looking down at us as we ran through the choreography from where the audience normally sat.

Or when we suddenly switched directions from where we had entered, and realised how used we were to our usual dance positions.

Or the time she made us wear skirts a month in advance so we’d get used to dancing in our costumes.

I’d brushed this off, thinking she was just preparing us for anything to go wrong, until I came across a Washington Post article about a study observing three groups learning a skill. The study concluded with observing that the group that performed best was the one that practiced with slight variations to the task.

The dots connected when I read the main takeaway from the study :

“If you practice the exact same thing the exact same way every time, you’re not layering much new knowledge over what you already know.”

No wonder we spent less time learning the choreography than we did practicing it.

Rest

I was pretty surprised to find articles and Reddit threads mentioning the importance of rest when it came to improving the performance of a skill. The “just sleep on it” rule actually applies here too. There’s evidence that after hitting a roadblock in picking up the skill, a full night’s rest can lead to noticeable improvement the next day.

Hitting a roadblock during practice was fairly normal for us. That’s usually when we’d be asked to stop and spend quite a bit of time just listening to the music and recovering from an intense session.

The final huddle before a performance would cover all sorts of things, but I always remembered how much she emphasised the importance of getting a good night’s sleep. I used to think it was just about managing pre-performance nerves, but now I realise it also had a real effect on how well we retained the choreography.

It’s still a mystery to me whether she consciously implemented these techniques, whether they were passed down to her, or if she just intuitively knew what to do. But I’m incredibly grateful to have experienced that. Looking back, I know I’ll keep asking myself: “Do I know my choreography?” And if not then “From ze beginning.”

Putting my Memory to the Test: 11 Years Later

I picked out one of the earliest pieces I ever learned — a basic invocatory item taught in Kuchipudi — to see how much of it I’d retained.

It’s been 11 years since I last practiced this piece. Here’s what came back to me:

Specific movements and gestures tied to lyrics I understood

Certain musical cues I had used as memory markers while learning

Spatial orientation: moving left vs. right, which leg to lift, where to go toward or away from

The distinct memory of when I wore my teacher’s red costume and performed this

The joy of dancing

I plan to keep exploring this, but for now I only have everything I’ve read and my own anecdotal experience to go on.

If you’ve got any resources, articles, videos, social media posts, books, research papers or even personal anecdotes on Muscle memory, send it over I’d love to see it!

And if you’ve got any questions about this topic, I’d love to find new ways to explore and answer them.